Table of Contents

- Understanding Currency Devaluation

- Pakistan’s Rupee Journey and Export Trends

- Why Exports Didn’t Rise as Expected

- Structural Barriers and Cost Pressures

- What Needs to Change

- Conclusion

1. Understanding Currency Devaluation

Currency devaluation means a deliberate reduction in the value of a country’s currency relative to others. In theory, this should make the country’s exports cheaper for foreign buyers and imports more expensive for local consumers. The expected result is an increase in exports, a decline in imports, and an improved trade balance.

For example, if the rupee weakens against the dollar, a Pakistani exporter receives more rupees for every dollar earned, making exports more profitable. On the other hand, imported goods become costlier, which should encourage local production and import substitution.

However, this textbook theory assumes that industries are efficient, have excess capacity, and can respond quickly to increased foreign demand. If domestic production costs rise simultaneously with devaluation, the expected benefits may not materialize. That is exactly what has happened in Pakistan’s case.

2. Pakistan’s Rupee Journey and Export Trends

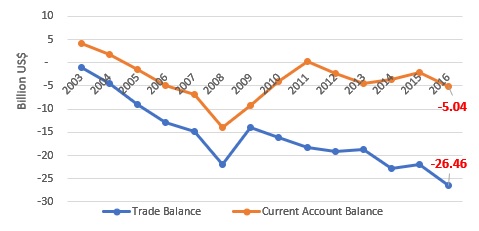

Over the last two decades, the Pakistani rupee has lost significant value against major global currencies. From around Rs 60 per US dollar in the early 2000s, it depreciated to over Rs 300 in 2023. Such a drastic fall should have made Pakistani goods more attractive to international markets.

Yet, export growth has been sluggish and inconsistent. The share of exports in Pakistan’s GDP has gradually declined, even as the currency weakened. Instead of rising, total exports have remained stagnant, and in some years, they have even fallen.

ALSO READ

Government Increases Petrol and Diesel Prices 5 Powerful Impacts You Must Know

This paradox indicates that while the rupee has lost value, the fundamental conditions necessary for boosting exports have not improved. The expected link between devaluation and export growth has simply broken down.

3. Why Exports Didn’t Rise as Expected

There are several reasons why the devaluation of the rupee has not led to the expected increase in exports.

Dependence on Imported Inputs

A large part of Pakistan’s export industries, especially textiles and chemicals, rely heavily on imported raw materials, dyes, machinery, and energy. When the rupee depreciates, the cost of these inputs rises sharply, offsetting the potential gain from cheaper export prices.

High Energy and Production Costs

Energy shortages and inflated electricity tariffs have been persistent issues. Devaluation increases the local cost of imported fuel, raising energy expenses across industries. High costs reduce profit margins, making Pakistani products less competitive globally.

Exchange Rate Volatility

Frequent and unpredictable fluctuations in the exchange rate create uncertainty. Exporters face difficulties in pricing their products and signing long-term contracts. Sudden currency crashes discourage investment and production planning, eroding confidence among exporters.

Narrow Export Base

Pakistan’s export base remains narrow, concentrated mainly in low-value textile products and a few agricultural commodities. This lack of diversification means the country cannot easily expand exports even if prices become more competitive.

For detailed trade and export data, visit the Ministry of Commerce Government of Pakistan.

Weak Industrial Structure

Devaluation works best in economies that have a diverse, productive industrial base. In Pakistan, structural weaknesses—such as poor logistics, outdated machinery, and low technological capacity—limit the ability of firms to scale up production when global demand rises.

4. Structural Barriers and Cost Pressures

Devaluation alone cannot overcome deep-rooted structural challenges. Instead, it often amplifies them. When the rupee weakens, the cost of imported raw materials, machinery, and fuel rises. These higher costs push up inflation and reduce purchasing power across the economy.

Pakistan also carries a large external debt burden denominated in foreign currencies. When the rupee loses value, debt servicing costs rise in local currency terms. This leaves the government with fewer resources to support export-oriented industries through subsidies, incentives, or infrastructure development.

Moreover, energy shortages, poor transport infrastructure, and bureaucratic inefficiencies further raise the cost of doing business. As a result, even when global demand exists, Pakistani exporters struggle to meet it competitively. Devaluation becomes a burden instead of a boost.

Other regional economies, such as Bangladesh and Vietnam, have demonstrated how stable policies, industrial diversification, and strong export facilitation can yield far better outcomes. Pakistan’s problem, therefore, lies not in devaluation itself, but in the absence of supporting reforms.

5. What Needs to Change

To make devaluation effective, Pakistan must address its structural and policy weaknesses.

- Ensure Macroeconomic Stability: Exchange rate movements should be gradual and predictable. Sudden depreciations create panic and disrupt business planning.

- Lower Energy and Logistics Costs: Reliable and affordable power, along with efficient transport and ports, is essential to improving export competitiveness.

- Diversify the Export Base: Expanding into higher-value products like pharmaceuticals, processed foods, and technology-based goods can reduce dependency on textiles.

- Strengthen Local Supply Chains: Developing domestic industries that produce raw materials and intermediate goods can reduce reliance on expensive imports.

- Encourage Technology Upgradation: Investing in modern machinery, research, and skills training increases productivity and product quality.

- Maintain Policy Consistency: Stable trade and industrial policies build trust among investors and exporters, encouraging long-term commitments.

By implementing these reforms, Pakistan can transform devaluation from a temporary shock into a sustainable advantage.

6. Conclusion

The devaluation of the rupee should, in theory, have strengthened Pakistan’s exports. In reality, it did not—because devaluation alone cannot overcome structural inefficiencies, high production costs, and an undiversified industrial base.

A weaker currency makes sense only when industries are capable, efficient, and well-supported. Without reliable energy, affordable inputs, and clear policies, devaluation becomes a source of inflation rather than growth.

Pakistan’s experience highlights an important lesson: currency devaluation is not a shortcut to competitiveness. Real export growth will come from reforms that enhance productivity, diversify industries, and create a stable, predictable business environment. Only then can a weaker rupee truly translate into stronger exports and a healthier economy.